Key points:

-

The COVID-19 pandemic pummelled Latino college enrollment rates. Latino enrollment fell 7% from fall 2019 to fall 2021. At community colleges, the decline was more than twice that.

-

Latino enrollment had grown 48% from 2009 to 2019. “It’s unbelievable how much COVID managed to reverse that,” Iowa State professor Erin Doran said.

-

Latinos are likelier to have family obligations and to work while in college.

In early 2020, Kristian Enbysk was excited about the next step in his postsecondary journey: Transferring from Grayson College, a community college in North Texas, to the University of North Texas in Denton, where he could study Latin American history.

Then came COVID-19. His father, a disabled vet and contract worker for a delivery service, struggled to find work as deliveries dried up. Enbysk considered dropping his university studies and getting a job to help his family. After discussing it with his parents, he ultimately decided to stay in school.

“Obviously the pandemic has been the cause of a lot of dysfunction,” said Enbysk, a Panama-born 23-year-old who came to the United States as an infant.

Around the country, enrollment numbers reflect similar challenges confronted by the nation’s approximately 3.7 million Latino undergraduate students: Enrollment among Latinos fell 7% from fall 2019 to fall 2021, according to the National Student Clearinghouse Research Center. At community colleges, the decrease was 15.7%.

Meanwhile, during the 2020-2021 school year, the number of Hispanic-serving institutions – a federal designation denoting schools with Hispanic populations of 25% or more – dropped for the first time in 20 years.

Deborah Santiago, CEO of Excelencia in Education, a national organization based in Washington, D.C., that analyzes Latino student data and promotes policies supporting Latino student achievement, blamed that downturn on lower Hispanic enrollment and institutions forced to close or consolidate because of the pandemic.

The decrease is not inconsequential: While Hispanic-serving institutions comprise just 18% of all higher-education institutions, they account for 66% of all Latino college students.

The declines are especially troublesome coming after a decade of enrollment gains for Latino students. From 2009 to 2019, Latino college enrollment rose from 2.4 million to 3.5 million, a 48% increase that made Latinos one of only two demographic groups to rise during that stretch, along with Asian Americans.

U.S. Department of Education estimates had projected that growth to continue, but the pandemic, Santiago said, exposed the house of cards that underlay the boom.

“It’s clear that the pandemic had an impact because of the economic vulnerability of the population,” Santiago said. “We had one of the highest college-going rates, but as students’ parents lost their jobs or got sick, they stepped in to help out.”

That was evident at schools like El Paso Community College, where administrators were unprepared for the drop, especially after seeing high enrollment numbers as late as summer 2020.

“We anticipated this would be like any other economic downturn,” said William Serrata, the school’s president. “Any time in the last 50 years when the economy went south, we saw a surge. But quite frankly, the bottom fell out.”

Overall enrollment fell 9.5% that year, Serrata said – and as of fall 2021, total enrollment at the school had fallen 15% in two years, from more than 29,000 students to less than 25,000. Latinos make up 85% of the school’s student body, he said.

With the school’s number of graduating students staying about the same, Serrata eventually deduced that younger students had abandoned their studies to join the workforce, especially as some employers increased wages to replace the high number of Americans who quit their jobs after the pandemic began.

“They were going into entry-level jobs, but they weren’t making minimum wage anymore,” Serrata said. “They were making $12 to $17 an hour. I don’t begrudge them at all. I just want them to plan for the future.”

While the dip in enrollment is starting to level out, Serrata said, the decrease in degree attainm

ent is a larger issue, he said.

“With the economy continuing to shift into a knowledge economy, if we can’t get students enrolled, they won’t be qualified for those jobs,” he said. “The pandemic wiped away about five or six years of progression. That’s going to be a challenge.”

Latinos more susceptible to pandemic challenges

Anne-Marie Nuñez, a professor of higher education at Ohio State University in Columbus, said several factors made Latino students more vulnerable to pandemic conditions. In addition to being likelier to work while attending school and to be saddled with family obligations, Latinos are also the least likely group to procure loans to pay for college, “so the role of jobs is even more important in their education,” Nuñez said.

In national surveys, Latinos reported more challenges than other groups in adjusting to online learning environments during the pandemic. They took longer to complete degree requirements, worried about losing jobs or supporting families, or had difficulty finding quiet places to study.

“When you add up all the uncertainty and precarity over money and mental health since March 2020, it’s no wonder that school just fell off many students’ radars,” said Erin Doran, an education professor at Iowa State University in Ames.

Doran said her peers had noticed a decline in Latino students even before the pandemic as the anti-immigrant rhetoric of the Trump administration raged, along with local raids conducted by U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement agents. Still, the degree to which national Hispanic enrollment fell after March 2020 came as a surprise.

“For people like me who have written sentences like, ‘Latino enrollment has been growing steadily for years,’ it’s unbelievable how much COVID managed to reverse that in a matter of a year,” Doran said. “I think it was all just too much – the mental health issues, the stress of being home all the time.”

Of all freshmen who started school in fall 2019, just 74% remained in school as of fall 2020, the first year of the pandemic, according to the National Student Clearinghouse Research Center. That represented a 2% rate drop over the previous year and the largest decrease since reporting began in 2009.

For Latinos, the decline was even greater. Just 68.6% of those who started as freshmen in fall 2019 remained in school as of fall 2020 — a 3.2% drop from the previous year and more than twice the decline among white, Asian American or Black students, the center said.

Vanessa Sansone, assistant professor of higher education at the University of Texas at San Antonio, said that because of their relative affordability, community colleges serve about half of all Latino students as well as a significant number of first-generation college students with greater financial needs.

“What the pandemic demonstrated to me is how fragile Latino post-secondary attainment and success was before any of this happened,” Sansone said. “It probably will continue for a long time after we come out of this. Because that’s all it took. It’s going to set us back a number of years.”

‘Students were needing more help than ever’

Some colleges and universities stepped up their outreach to Latino families and students to reverse the losses from the pandemic.

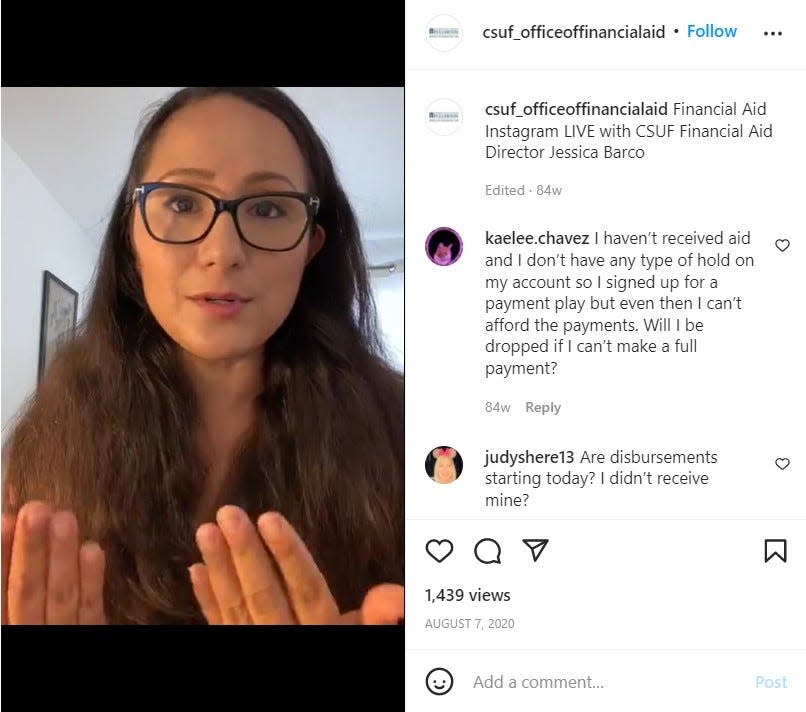

At California State University, Fullerton, where Hispanic students are 47% of the population, financial aid office staff used technology and social media to address pandemic-related student concerns.

In the summers of 2020 and 2021, as deadlines approached for student financial aid applications, director Jessica Barco conducted Instagram Live sessions to answer student questions, and staff called students individually to ask about life changes that might qualify them for additional aid.

When student applications for federal aid and Dream Act funding for undocumented students trended downward in 2020, Barco’s office crafted instructional videos on both. Students unsettled by the

pandemic were urged to apply for aid anyway, and they responded, flooding the office with emails and phone calls.

“Students were needing more help than ever,” Barco said. “They were asking, ‘Do you have anything else you can give?’ I went on Instagram Live and told them they could apply for income appeal. Students can feel like they’re in a dark room, not knowing who’s going to guide them. We had to get creative and more accessible.”

Students at California State University, Fullerton, must maintain at least a 2.0-grade point average and pass at least two-thirds of their classes or risk losing financial aid. They can also be dropped from classes for non-payment, so Barco’s office set aside discretionary institutional funds for 11th-hour aid to keep students enrolled.

This spring, Barco said, the office used $3.6 million to save 946 students, 60% of them Hispanic, from disenrollment.

The work has paid off. Financial aid applications at the school rose 15% in 2020-2021 and another 1% this year, Barco said.

At San Antonio College in Texas, enrollment held firm through the pandemic, largely through strong messaging that told students they were better off with the school than without it. Even taking one class could qualify students for school resources, including mental health services or assistance with housing and food insecurity.

“We did lose some students, but not at the degree we saw nationally,” said Robert Vela, the school’s president. “What may have dipped is the amount of classes they were taking.”

As part of retention efforts, the school used federal money to turn parking lots and outdoor areas into connectivity-ready workspaces, upgrading Wi-Fi access and making laptops and hotspots available for checkout. The effort addressed not only technology access issues but also offered a quiet space outside cramped homes for students to get work done.

“We knew the college was kind of their safe haven,” Vela said. “Now they can drive into the parking lot or sit at a picnic table and have a great connection with no interruptions. We didn’t want our students to not progress simply because they didn’t have the right tech or coverage.”

The project was well-received by the school’s Latino students, about two-thirds of the student population.

“We heard good things from students, from families that only had one computer, who were sharing it with their elementary-school brother or their mom, or who didn’t have the right bandwidth at home to support the streaming that they needed,” Vela said.

Vela expects the program to continue now that the pandemic has reshaped how college administrators and professors see the process of delivering education.

“I think we would misstep if we said, let’s go back to pre-pandemic environments,” Vela said. “We understand what our students need to matriculate and graduate. I strongly support having this beyond the pandemic to make sure they have their technology needs met, whether it’s here or virtually.”

Enbysk, now a fifth-year student at the University of North Texas, is glad he stayed in school. His sister had faced a similar decision even before the pandemic, he said; she opted to work, got a good-paying job and never returned to college. That factored into his decision to obtain his degree, he said.

Enbysk serves as treasurer of the school’s Hispanic Student Association and while he still struggles to keep up with tuition and housing costs, he enjoys the diverse campus atmosphere, which has helped him explore his Hispanic heritage after growing up in a tiny, mostly white city in rural Texas.

“I’m conflicted because sometimes I feel too white for Latinos, and too brown for whites,” he said. “I’m trying to find a balance, trying to get accepted, and it can be difficult mentally, but I’ve learned to process and do the best I can.”

Discussions with other students in the group — about financial struggles, about self-identity — help keep him grounded.

“They’re just as different as I am, and that’s okay,” Enbysk said. “They have the same issues. We’re all going through the same thing, so we might as well do it together.”

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: Latino college students dropped out, quit classes during COVID-19